Nineteen sixty-nine was a tumultuous year

It was the year I started to learn how to rebel.

As a teenager in Perth, the most isolated city in the world, news arrived days or weeks later than for the rest of the world.

The Vietnam War was the most pressing for me because I was only a few years away from the threat of conscription.

Many forget or don’t realise that it wasn’t only teenagers in the United States who were conscripted to fight the dirty war in Vietnam.

Since its federation in 1901, Australia has fought in every war alongside the United States.

So even though I was half a world away, my fate was going to be decided by the new United States President, Richard Nixon.

I spent my high school years marching in war protests, chanting anti-war slogans and learning to rebel against the establishment.

Restricted, prohibited, banned

I was more Rolling Stones than Beatles. More Led Zepplin than Bob Dylan.

It was the year that I discovered John Lee Hooker. In doing so, I also learned about government hypocrisy and unfairness.

There was every likelihood that I would be conscripted to fight America’s war in Vietnam. Yes, I could die for the United States, but I wasn’t American enough to be able to buy John Lee Hooker records at my local record store.

Even though they were close allies, trade between the United States and Australia was highly restricted.

Due to U.S. copyright law, it was difficult to buy records by many U.S. artists. At the time, cover versions of popular songs were recorded by local artists in countries outside the United States.

Circumventing these laws was possible, but it was a long and expensive process. There was one record store in the city centre of Perth that specialised in importing records.

I can still remember the strong smell of incense when you entered the store, which was seemingly trying to cover the odour of marijuana. The walls, ceiling and floor were black, with peace signs painted on the left and right walls.

The owner was an ageing hippie. Well, for me that is. He was probably in his late thirties.

But he had connections, and for a price, he could get almost any U.S. record. My John Lee Hooker records cost me ten times the regular price for an LP, and I had to wait for months.

It didn’t matter though. With each record I bought, I had succeeded in defying the stupid law.

The last banned book

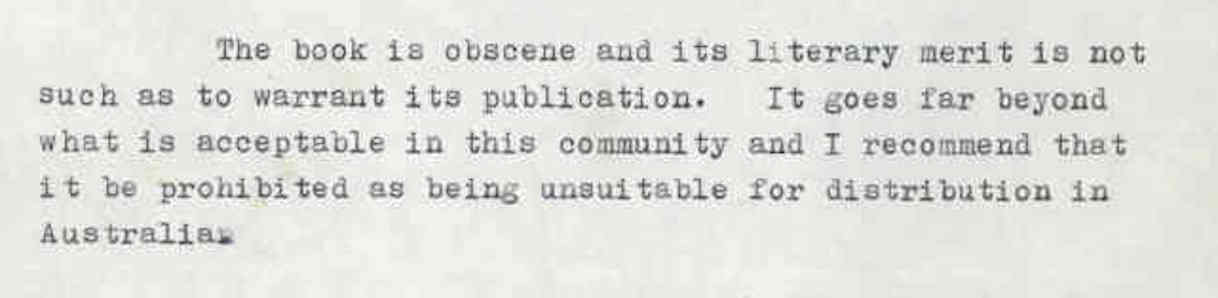

In 1969, a new book was declared a prohibited import in Australia. In other words, it was banned by the government.

It took some time for the news to reach my remote part of the world, but it became an immediate talking point amongst my friends.

What type of country were we living in? What right did the government have to decide what we could read?

The book in itself didn’t matter. At the time we didn’t even know what the book was about. All we knew was that the book was called Portnoy’s Complaint and the author’s name was Philip Roth.

But of course, because it was banned, we now wanted to read it.

In a totally absurd situation, the Australian publisher, Penguin Books, dodged the import ban by secretly printing copies of the book in Sydney and storing them in fleets of constantly moving trucks to avoid being seized by the government under state obscenity laws.

However, Penguin was successfully prosecuted in Victoria and Queensland.

In South Australia, the state government declared that it would not prosecute if the book was sold to an adult who made a direct request of the vendor and provided that the books were kept behind or under the counter.

Where I lived in Western Australia however, the prosecution was ultimately unsuccessful because works of recognised artistic, scientific or literary merit were immune under the local statute, even if they may have been classified as obscene.

It wasn’t until late 1970 that I was able to buy a copy of Portnoy’s Complaint.

I preferred Lord of the Flies

I had to read it, didn’t I? It was banned so it had to be a must-read.

The story of a young Jewish bachelor, Alexander Portnoy is told in narration to his psychoanalyst, Dr Spielvogel. The novel is set mostly in New Jersey between the nineteen-forties and the nineteen-sixties.

It was the time of the sexual revolution, but the heavy references to Alexander’s sexual acts and the notorious piece of liver were still of course scandalous.

But for me, as a teenager, the story about a young man from a Jewish family didn’t really grab me. Perhaps it was from living so far away from the world that there were many aspects I didn’t understand.

One quote from the book, “Doctor doctor, what do you say, let’s put the id back in yid,” lost me because I had no idea about Yiddish at the time.

Yes, it was a prize-winning banned book. But that I didn’t succeed in getting to read it while it was still banned counted as a failure to me. I hadn’t fought and won.

The book became a line in the sand for Australian censorship law. It was the last time the censorship of a literary publication appeared before the courts. In June 1971, the book was removed from the federal banned book list.

Newark, New Jersey

Newark has served as the backdrop for many of Roth’s novels, in which he narrates the Newark tales exuberantly, from a flourishing blue-collar melting pot, through shrinking of its industrial base, to the 1967 riots, and its decline.

Founded in 1666 by a small group of Puritans from Connecticut, who purchased land along the Passaic River from the Lenni-Lenape Indians, Newark soon emerged as America’s first industrial centre.

In the Jewish neighbourhoods that Roth knew in the 1930s and 1940s, settled Eastern European immigrants who arrived from the early 1880s through the mid-1920s. Some 50,000 made their way to Newark. They lived initially in tenements in and around Prince Street, in the city’s old Third Ward.

That’s when Roth’s grandparents arrived. Roth’s paternal grandfather worked in the tanneries to put food on the table for seven kids, including Roth’s father, Herman.

In The Facts, Roth explains that they left Europe “because life was awful; so awful, in fact, so menacing, or impoverished or hopelessly obstructed, that it was best left forgotten.”

In The Plot Against America, he writes that “though Ireland still mattered to the Irish and Poland to the Poles and Italy to the Italians, we retained no allegiance, sentimental or otherwise, to those Old World countries that we had never been welcome in and that we had no intention of ever returning to.”

This willingness to forget their European past is what separated Newark’s Jews from many of the other immigrants and explains why assimilation was so important for them.

As the Jewish immigrants’ children embraced Americanness, they gradually formed a lower-middle-class ethnic stronghold known as Weequahic, an Indian phrase meaning “head of the cove.” That’s where Roth grew up.

Today, relatively few Jews still live within Newark’s city limits. But when Roth was growing up, between 60,000 and 70,000 Jews out of a total city population of about 450,000 lived in Newark, many of those in the Weequahic neighbourhood.

The Plot Against America includes descriptions of what life in Weequahic may have been at the time, centred around a strong sense of family values and a lot of very hard work.

Roth depicts the working men, the children of the first Jewish immigrants who strived to make their children’s lives better than their owns: “The neighbourhood men either were in business for themselves . . . or the proprietors of tiny industrial job shops . . . or self-employed plumbers, electricians, house painters and boilermen—or were foot-soldier salesmen like my father, out every day in the city streets.” These men, Roth recounts, “worked fifty, sixty, even seventy or more hours a week.”

Their wives took on every other family task. “The women worked all the time . . . washing laundry, ironing shirts, mending socks, turning collars . . . cooking meals, feeding relatives, tidying closets and drawers . . . paying bills and keeping the family’s books while simultaneously attending to their children’s health, clothing, cleanliness, schooling, nutrition, conduct, birthdays, discipline and morale.”

In his early works, especially in Portnoy’s Complaint, Roth describes how when growing up in such an environment, one can feel suffocated and struggle between Judaism and Americanness, between a feeling of belonging and alienation. Accused of portraying Jews in an unflattering light, he was loudly critiqued by many in the Jewish community.

Yet later, he became more sympathetic towards his father’s generation: “They had a task, an American task, and a particular cultural burden”, Roth noted in 1991. “Newark is the battleground, one of many cities in this country, on which the struggle took place. The job they had was to stand between the European family of their immigrant parents and the American realities of their younger children. They were a generation of negotiators, of constructors.”

In Patrimony, Roth writes about the city’s sad decline. Visiting old neighbourhoods he finds that “what in my childhood had been the busy shopping thoroughfares of a lower-middle-class, mostly Jewish neighbourhood were now almost entirely burnt out or boarded up or torn down”.

In Zuckerman Unbound, Nathan Zuckerman observes, “But for candles, incense, and holy statuary, nothing seemed to be for sale anymore on Lyons Avenue. There didn’t seem to be anywhere to buy a loaf of bread or a pound of meat or a pint of ice cream or a bottle of aspirin. . . Their little thoroughfare of shops and shopkeepers was dead.”

American Pastoral, set during a time of great political unrest in America describes several historical events, including the Newark race riots, and centres on how the 1960s’ national cultural and political turbulence destroys Levov’s family. Swede Levov observes: “Springfield Avenue in flames, South Orange Avenue in flames, Bergen Street under attack, sirens going off, weapons firing . . . looting crowds crazed in the streets.”

Of Railroad Avenue, Swede Levov says: “Along this forsaken street, as ominous now as any street in any ruined city in America, was a reptilian length of unguarded wall barren even of graffiti. But for the wilted weeds that managed to put forth in wiry clumps where the mortar was cracked and washed away, the viaduct wall was barren of everything except the affirmation of a weary industrial city’s prolonged and triumphant struggle to monumentalize its ugliness.”

“The old Jews like my grandparents had struggled and died, and their offspring had struggled and prospered, and moved further and further west, towards the edge of Newark, then out of it, and up the slope of the Orange Mountains, until they had reached the crest and started down the other side, pouring into Gentile territory.” — Goodbye Columbus

Roth has been criticised for giving a stereotypical description of Newark’s decline, a familiar narrative of bigoted whites fleeing to the suburbs as blacks arrived in the city. However, as Steven Malanga explains, “Roth’s stories reject the easy, conspiratorial view that Newark and other cities started to die because of a plot against them by government planners in favour of growing suburbs, exacerbated by white racism”.

Philip Roth’s Newark

Philip Roth was born in Newark Beth Israel Hospital on 19 March 1933, and his childhood home at 81 Summit Avenue in Weequahic is still standing. It is where Roth and his family resided in a five-room flat on the second floor of a multi-family home

He attended the Weequahic High School 279 Chancellor Ave, only a block away from the family home. Alexander Portnoy of Portnoy’s Complaint went there, too.

“Ikey, Mikey, Jake and Sam

We’re the boys who eat no ham

We play football, we play soccer—

And we keep matzohs in our locker!

Aye, aye, aye, Weequahic High!”

— Portnoy’s Complaint

The 1899 Newark Public Library is where the fictional Neil Klugman in Goodbye, Columbus worked with a colleague working with a colleague whose “breath smells of hair oil and hair oil of breath”.

In March 1969, nineteen months after riots had devastated Newark, Philip Roth wrote an article in the New York Times pleading to save the city’s library that the Newark City Council threatened to close: “When I was growing up in Newark,” wrote Roth, “we assumed that books in the public library belonged to the public. Since my family did not own many books, or have the money for a child to buy them, it was good to know that solely by virtue of my municipal citizenship I had access to any book I wanted from that grandly austere building downtown on Washington Street.”

Fortunately, the City Council found the money to keep the library opened.

When he died in May 2018, Roth willed his personal book collection to the Newark Public Library. According to the terms of his will, the library has three years from the date of his death to create the Philip Roth Personal Library, which will be housed on the second floor of the building.

Salman Rushdie honoured the memory of Philip Roth by giving the Newark Public Library’s annual Philip Roth Lecture on 27 September 2018. The lecture, which the Forward published in full, was the third of its kind. As was the case with previous speakers Zadie Smith and Robert Caro, Roth himself asked Rushdie to deliver the talk.

The Newark Museum is where Philip Roth celebrated his eightieth birthday in 2013.

In Goodbye, Columbus, the narrator, Neil Klugman, while sitting in Washington Park recalls: “I could see it without even looking; two oriental vases in front like spittoons for a rajah and next to it the little annex to which we had traveled on special buses as schoolchildren.”

Of Washington Park Neil Klugman in Goodbye, Columbus says: “The park … was empty and shady and smelled of trees, night and dog leavings; and there was a faint damp smell too, indicating that the huge rhino of a water cleaner had passed by already, soaking and whisking the downtown streets.”

Weequahic Park is described in The Plot Against America: “… a landscaped three hundred acres whose boating lake, golf course and harness-racing track separated the Weequahic section from the industrial plants and shipping terminals lining Route 27 and the Pennsylvania Railroad viaduct east of that and the burgeoning airport east of that and the very edge of America east of that — the depots and docks of Newark Bay where they unloaded cargo from around the world.”

On Clinton Ave, sits the Riviera Hotel, which the narrator of The Plot Against America, who happens to be named Philip Roth, describes as the spot his parents spent their wedding night.

First opened in November 1922, the hotel has an interesting history.

Longy Zwillman, the notorious member of the “Jewish Mafia”, used the Riviera as his Third Ward residence in the 1930s.

The Riviera never recovered from the Great Depression. In 1949 it was sold to George Baker, aka “Father Divine”, who added the “Divine” to the name. Father Divine bought the 250 room hotel for cash!

It took 14 bank tellers three and a half hours to count all the $1s, $5s, $10s, and $20s. For the next few years, the Divine Hotel Riviera was run as one of Father Divine’s “Heavens.”

There was no alcohol sold, and men and women had to be lodged separately.

Looking at the reviews on Tripadvisor, it seems that the hotel, which is a beautiful building, has unfortunately never been upgraded.

Still on Clinton Avenue, Roth (both author and narrator of The Plot Against America) describes the Temple B’Nai Abraham (also known as Deliverance Temple and Deliverance Evangelistic Center), a historic synagogue and church built in 1924: “Temple B’nai Abraham, the great oval fortress built to serve the city’s Jewish rich and no less foreign to me than if it had been the Vatican.”

Essex County Courthouse, dating to 1904, is another landmark honoured by Newark and Roth alike: the bronze statue by famed Mt. Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum of Lincoln, “seated and waiting welcomingly on a marble bench before the courthouse, in his social posture and by his gaunt, bearded face revealing that he is wise and grave and fatherly and judicious and good,” Roth wrote in I Married a Communist.

About Phillip Roth in brief

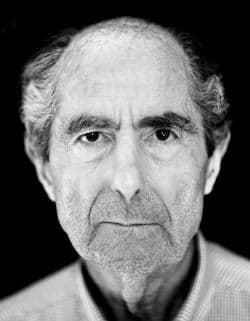

Philip Milton Roth was born on March 19, 1933, in Newark, New Jersey. He passed away on May 22, 2018, in Manhattan, New York.

Roth’s first book, Goodbye, Columbus, contains the novella Goodbye, Columbus and four short stories. It won the National Book Award in 1960.

His fourth and most controversial novel, Portnoy’s Complaint was published in 1969 and gave him widespread commercial and critical success.

He received the Pulitzer Prize in 1997 for his novel American Pastoral. The book featured one of his best-known characters, Nathan Zuckerman, a character Roth used in many of his novels.

In 2000, The Human Stain, another Zuckerman novel, was awarded the United Kingdom’s WH Smith Literary Award for the best book of the year.

In 2001, in Prague, Roth received the inaugural Franz Kafka Prize.