Walk the streets of Geneva in Switzerland to discover the answer

Life was complicated for Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, and everybody else around her.

Mary Shelley (née Godwin) was born in London in 1797. Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was a writer, philosopher, and advocate of women’s rights. Her father, William Godwin was a journalist, novelist and anarchist philosopher.

Mary’s half-sister, Fanny Imlay, who was three years older than her, was born after her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, had an affair with an American businessman, author and diplomat, Gilbert Imlay, before she met Godwin.

Mary’s mother died a short time after she was born and she was raised, along with her half-sister, by her father.

In 1801, four years after the death of Mary Wollstonecraft, Godwin married his neighbour, Mary Jane Vial Clairmont. She already had two of her own children, Claire and Charles. Very little is known about the life of Mary Jane Vial Clairmont before she met William Godwin and her past remains a mystery. The new couple soon became the parents of a son, William Godwin Jr.

Godwin was responsible for a family of five children, none of whom had the same two parents, but all of whom had a mother called Mary.

Mary’s affair with romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley started in 1814 when she was 16. Percy, a devoted disciple of William Godwin, with whom he shared his philosophy, was a proponent of vegetarianism, non-violent action and free love. Despite that, he married twice.

At the time, Percy Shelley fell in love with Mary, he was married to Harriet Westbrook. In July 1814, when Mary ran away to Europe with Percy, she was pregnant. The couple was accompanied by Claire Clairmont, with whom Mary had developed a close relationship. Together, the three took a six-week tour through France, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland.

In November 1814 his wife Harriet bore a son, and in February 1815 Mary gave birth to a child who died two weeks later.

In December 1816 Harriet Shelley apparently committed suicide by drowning in the Serpentine River in Hyde Park, London. She was pregnant. She was only 21.

A few months earlier, in October of the same year, Mary’s older half-sister, Fanny Imlay, committed suicide in Wales.

Percy Shelley later married Mary Godwin, losing custody of his two first children.

In July 1822, Percy Shelley was just 29 when he drowned in Italy, after his boat, Don Juan was caught in a storm. Mary was only 24.

The dramatic death of Percy Shelley was set to become one of the most powerful of all Romantic legends. There are many conspiracy theories about the circumstances of Shelley’s death and funerals.

In keeping with quarantine regulations, which made it necessary for the bodies of the drowned to be burned, Shelley was cremated on the beach near Viareggio and his remains later buried at the Protestant cemetery in Rome.

An 1889 painting by Louis Édouard Fournier, The Funeral of Shelley, shows the funeral pyre surrounded by three of the dead poet’s closest friends, Lord Byron, Leigh Hunt and Edward John Trelawny, and in the background, Mary Shelley.

It is a beautiful painting, but not an accurate depiction of the event. It was actually a bright and sunny day, not overcast, and Mary Shelley did not attend the cremation. Lord Byron was so repulsed by the whole thing that he decided to go for a swim instead of watching the cremation, so he could not be in the picture.

There is one rumour about Shelley’s death that is believed to be true. The poet’s heart resisted the flames, was plucked from the ashes and given to his widow, Mary. After her death, the heart was discovered wrapped in the pages of one of his last poems, Adonais.

In Trelawney’s own account of the event, in Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron, he described:

“The only portions that were not consumed were some fragments of bones, the jaw, and the skull, but what surprised us all was that the heart remained entire. In snatching this relic from the fiery furnace my hand was severely burnt.”

After her return to England, she set out to create a collection of Percy’s Posthumous Poems (1824). Mary herself wrote a short introduction to the poetical works. It was her first opportunity to share publicly her recollection of the poet’s character. She recalled his love of nature and solitude; his fragile health; his enthusiasm for a sacred cause, ‘the improvement of the moral and physical state of mankind’; his transparent goodness and intellectual brilliance.

Later, Mary Shelley will write her a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel The Last Man (1826), as a literary tribute and memorial to her husband and Lord Byron. It was also a way for her to circumvent the prohibition placed on publishing a biography of Percy Bysshe Shelley by her father-in-law. One of the main characters, Adrian, who leads his followers in search of a natural paradise and dies when his boat sinks in a storm, was an idealised portrait of her husband. The other main character, Raymond, who leaves England to fight for the Greeks and dies in Constantinople is based on Lord Byron.

A summer of rain

In May 1816, Percy Shelley, Mary Goodwin (they only married in late 1816), their son William, and Claire Clairmont, who in the meantime had initiated a liaison with Lord Byron, travelled to Geneva, where Mary Shelley conceived the idea for her novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

Byron rented the Villa Diodati in the leafy Geneva suburb of Cologny from 10th June to 1st November 1816. Percy Shelley rented a smaller building on the waterfront nearby called Maison Chapuis.

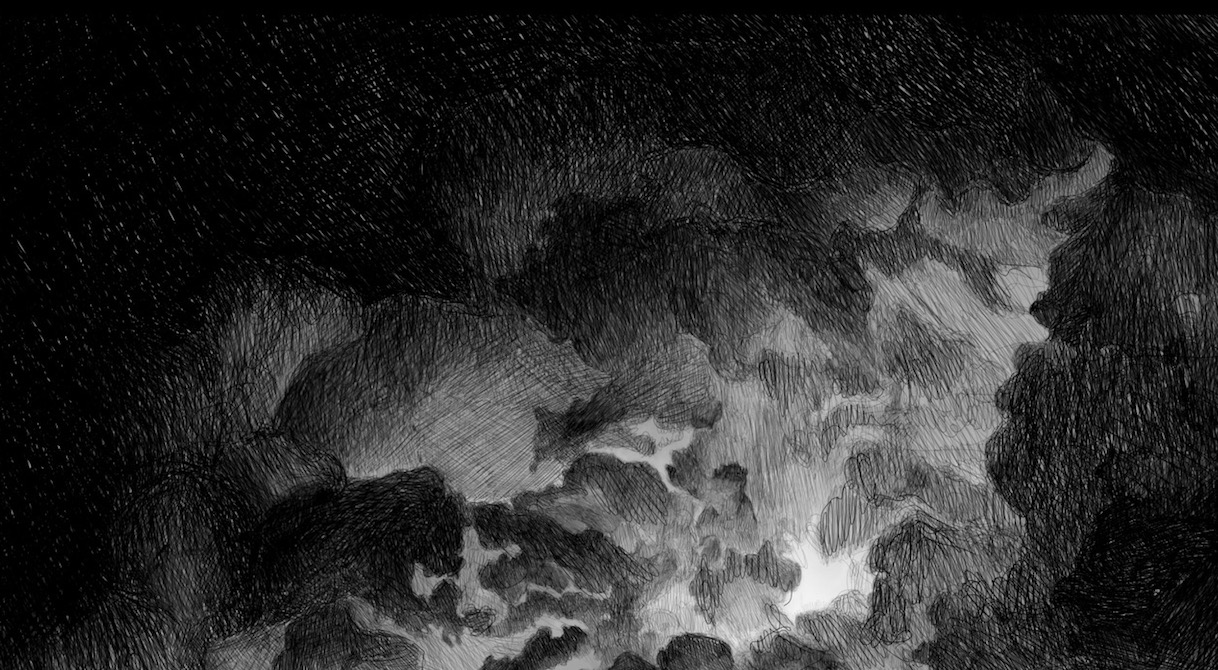

In April 1815, a volcanic eruption at Mount Tambora on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa was believed to be the cause of a summer of storms and torrential rain in Geneva in 1816. An event not explained at the time, it has become known as the “Year without Summer”.

Following the eruption at Mount Tambora, large amounts of sun-obscuring ashes and gases were emitted into the atmosphere and affected weather patterns around the planet. What happened this year throughout Europe and the US were very bizarre events: snow in July, frosts in August, heavy rain, weird animal die-offs, crop failures, famines and religious panics.

The apocalyptic weather of summer 1816 inspired Lord Byron who wrote his poem “Darkness” while in Geneva:

“I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air”

In a letter to her half-sister Fanny Imlay, Mary Shelley writes:

“One night we enjoyed a finer storm than I had ever before beheld. The lake was lit up—the pines on Jura made visible, and all the scene illuminated for an instant when a pitchy blackness succeeded, and the thunder came in frightful bursts over our heads amid the blackness”

The horrid weather meant that the touring party were indoors during much of their stay.

To occupy themselves, they started reading an anthology of German ghost stories, Fantasmagoriana, which inspired them to write their own zombie stories.

How to explain that a young woman found the inspiration to write Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, which will become one of the most iconic horror stories of all time?

Mary’s explanation in the introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein was that the story came to her in a dream:

“When I placed my head on my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness far beyond the usual bounds of reverie. I saw—with shut eyes, but acute mental vision—I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handiwork, horror-stricken . . . . He sleeps; but he is awakened; he opens his eyes; behold the horrid thing stands at his beside, opening his curtains, and looking on him with yellow, watery, but speculative eyes.

I opened mine in terror. The idea so possessed my mind, that a thrill of fear ran through me, and I wished to exchange the ghastly image of my fancy for the realities around. I see them still: the very room, the dark parquet, the closed shutters, with the moonlight struggling through, and the sense I had that the glassy lake and white high Alps were beyond. I could not so easily get rid of my hideous phantom; still it haunted me. I must try to think of something else. I recurred to my ghost story, —my tiresome unlucky ghost story! O! if I could only contrive one which would frighten my reader as I myself had been frightened!

Swift as light and as cheering was the idea that broke in upon me. “I have found it! What terrified me will terrify others; and I need only describe the spectre which had haunted my midnight pillow.” On the morrow I announced that I had thought of a story. I began that day with the words, It was on a dreary night of November, making only a transcript of the grim terrors of my waking dream.”

However, Frankenstein is more than just the transcription of a dream. It is simultaneously the first science-fiction novel, a Gothic horror, an adventure and travel book, a political metaphor, a tragic romance and a fable.

The initial impetus for the story was not political; rather, she wanted to write a ghost story, to prove herself as a writer. However, behind the Gothic narrative, pressing questions about playing god, race, class and science are woven into the story and reflect the discourses of the French Revolution, which was still fresh in the minds of romantic poets.

The scientific theories and experiments of the time are another likely source of influence for her story. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there were numerous experiments conducted with electricity, such as trying to revive a man who has just been hanged.

But there is another dimension, just as fundamental. Mary voices her anxiety of pregnancy, childbirth, motherhood and death. She wrote the story of Frankenstein, only two years after she lost her first baby. She was nursing her second child, William. By the time she finished her story, she was likely pregnant for the third time. In her life, she gave birth to five children, but only one lived to adulthood.

The return to Cologny

In 1840, in her late forties, ten years before her death, Mary Shelly returned to Cologny and wrote:

“The far Alps were hid, the wide lake looked drear. At length I caught a glimpse of the scenes among which I had lived, when first I stepped out from childhood into life. There on the shores of Bellerive stood Diodati; and our humble dwelling, Maison Chapuis, nestled close to the lake below. There were the terraces, the vineyards, the upward path threading them, the little port where our boat lay moored. I could mark and recognise a thousand peculiarities, familiar objects then, forgotten since now replete with recollections and associations. Was I the same person who had lived there, the companion of the dead for all were gone? Even my young child, whom I had looked upon as the joy of future years, had died in infancy. Not one hope, then in fair bud, had opened into maturity; storm and blight and death had passed over, and destroyed all. While yet very young, I had reached the position of an aged person, driven back on memory for companionship with the beloved, and now I looked on the inanimate objects that had surrounded me, which survived the same in aspect as then, to feel that all my life since is an unreal phantasmagoria the shades that gathered round that scene were the realities, the substances and truth of the soul’s life which I shall, I trust, hereafter rejoin.”

— Rambles in Germany and Italy, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, 1844

Frankenstein’s monster in Geneva

For the circle of friends at villa Donatti, Geneva was above all the city of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose political philosophy influenced the progress of the Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolution and the development of modern political thought. During the sojourn of Lord Byron, Mary Shelley, and Percy Shelley there in 1816, they read and wrote about him extensively.

Geneva once condemned Jean-Jacques Rousseau and burned his books, but today, a famous statue of Rousseau created by James Pradier in 1835 faces the city that turned its back on him. You will find it on Ile Rousseau, which can be accessed by the bridge called Pont des Bergues.

Victor Frankenstein was born in Naples, Italy (according to the 1831 edition of Shelley’s novel) and raised in Geneva:

“I am by birth a Genevese; and my family is one of the most distinguished of that republic. My ancestors had been for many years counsellors and syndics; and my father had filled several public situations with honour and reputation.”

Frankenstein’s monster commits his first murder, the killing of Victor’s youngest brother, William, just outside the ramparts of Geneva in Plainpalais, to which Mary had attributed political significance in History of a Six Weeks’ Tour (1817):

“To the south of the town is the promenade of the Genevese, a grassy plain planted with a few trees, and called Plainpalais. Here a small obelisk is erected to the glory of Rousseau, and here (such is the mutability of human life) the magistrates, the successors of those who exiled him from his native country, were shot by the populace during that revolution, which his writings mainly contributed to mature, and which, notwithstanding the temporary bloodshed and injustice with which it was polluted, has produced enduring benefits to mankind, which all the chicanery of statesmen, nor even the great conspiracy of kings, can entirely render vain. From respect to the memory of their predecessors, none of the present magistrates ever walk in Plainpalais.”

Today, Dr Frankenstein’s creature still lurks in Geneva.

His bronze statue stands on the Plaine de Plainpalais, next to a skatepark (Boulevard Georges-Favon, across the road from the Eglise du Sacré-Coeur), at the place where he committed his first murder of William.

La Plaine de Plainpalais is home to Geneva’s best flea market and farmers’ market. Many of the University buildings are located in the neighbourhood, a stone’s throw away from the abundant offer of bars, cafés and restaurants. Try Rue de l’Ecole de Médecine, a popular haunt for the young and not so young Genevois.

When the monster runs away, he climbs Mont Salève, the mountain where the Genevois love to spend their Sundays.

From the Salève, the view over Geneva, and also the Jura, the French Alps and the Mont Blanc, is truly amazing, when the sky is clear. But it is also a nice place to go when the winter fog hovers on the plain, to get a bit of sunshine and enjoy a unique atmosphere.

Though it is in France, the station of the Téléphérique du Salève (cable car) is easily reached from Geneva by public transport.

In five minutes, the Téléphérique will transport you to Mont Salève, at an altitude of 1,100 metres. There are several hiking trails on the Salève, including one to the Grand Salève at 1,379 metres. It is also a good place to go paragliding, rock climbing, mountain biking or cross-country skiing in winter. Or to enjoy the view. Or to read Shelley’s Frankenstein. Or just to enjoy a meal at the panoramic restaurant…

For the brave at heart, there are dozens of hiking trails going up to Saleve, varying from mild difficulty to very steep and dangerous ones. Normal hiking time from the bottom all the way up to Mont Saleve is about 3 hours.

On Sundays, you can join the Association Genevoise des Amis du Salève (Geneva Friends of Salève Association) for the hike. A good way to get to meet the locals. And it’s free!

The Villa Diodati in the village of Cologny is in private hands and can only be visited from outside a massive security fence.

The best place to catch a glimpse of the Villa is from the Pré Byron (Chemin de Ruth 9, Cologny), a public park that offers breathtaking views of Geneva. It is easily accessible by public transport.

Not far from Pré Byron, you will find the Martin Bodmer Foundation. This modern edifice by top Swiss architect Mario Botta is home to a unique treasure trove of the written word, with some 150,000 documents. The Foundation is one of the world’s biggest and greatest private libraries. A truly amazing place for history and book lovers!

The modern incarnations of Frankenstein

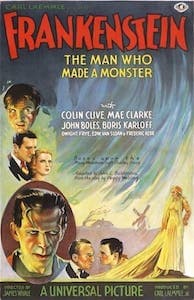

The 1931 film, starring Boris Karloff and directed by James Whale is perhaps the starting point for the current interpretations of Shelley’s book.

However, the imagery is totally different from the original Shelley monster as depicted by the Geneva statue.

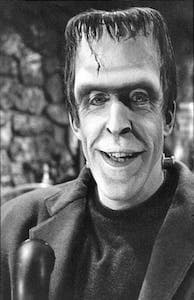

Through decades, the depiction of Frankenstein’s monster has been extremely similar, as the original movie and Herman Munster of the 60’s TV series illustrates.

I am not sure what Shelley would think about the flat head and bolt through the neck.

There have been many adaptations, variations and re-makes. Son of Frankenstein was another Universal monster movie with Boris Karloff made in 1939.

In 1932 came The Ghost of Frankenstein, in 1957 The Curse of Frankenstein and in 1965, Frankenstein Conquers the World.

Later adaptations included Young Frankenstein, directed by Mel Brooks in 1974, and then in 1975, The Rocky Horror Picture Show movie became a cult classic as Frankenfurter created his beautiful monster.

In 2015 came The Frankenstein Chronicles, a British television series, starring Sean Bean as John Marlott and Anna Maxwell Martin as Mary Shelley.

Undoubtedly, Mary Shelley’s story will continue to inspire readers and filmgoers for years to come. It is the quintessential horror story. It has been and will continue to provide stimulation for movies, books, and even games.

If you ask anyone to name one horror story, it would be surprising if it wasn’t Frankenstein’s monster.

Frankenstein today

The story of Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley has been reprinted by many publishers and is available in a whole host or editions.

If you haven’t read the story, it is widely available in all formats including ebook, paperback, audiobook and video.

No story has fascinated readers more for 200 years than Frankenstein’s Monster. It truly is one of the all-time classics and a must read for all literature lovers.

But it is surprising to learn that it was written in Geneva, Switzerland, by a very young 18-year-old woman.