The ancestor of crime and detective novels

The Woman in White, written in 1859 by Wilkie Collins, was a hugely successful novel.

It first appeared in a serial form in the All the Year Round, a British weekly literary magazine founded and owned by Charles Dickens, Collins’ friend, boss, and mentor.

The serial’s success was such that it became a dinner-table topic and that bets were struck as to the outcome of the story.

A Woman in White perfume was produced, Woman in White fashion became trendy, and Woman in White waltzes were danced in ballrooms.

At the time, readers in Victorian England were seduced by gothic literature, a genre introduced in the 18th century and named by Horace Walpole with The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story (1764). In gothic novels, terrible supernatural things would happen in gloomy remote places and in a romanticised past.

What was new about Collins’s novel was that it combined Gothic horror with psychological realism.

Scary situations, intricate plots around issues such as mistaken identity, insanity and inheritance happened in a real-life setting, making the reader believe it could happen to them. The characters, brilliantly developed, were complex, fascinating and realistic.

A contemporary journalist, Edmund Yates, one of Collins’ friends, described Wilkie Collins as a master of “the creepy effect, as of pounded ice dropped down the back”.

Interestingly, another thing that Collins experimented with for the first time was the structure of multiple narratives.

In The Woman in White, each character adds a piece to the puzzle of the story and offers different and contradictory perspectives. Collins said he had been inspired by criminal trials, in which witnesses tell what they know, or what they think they know about events.

Considered the first sensation novel, many have seen in The Woman in White the ancestor of crime and detective fiction novels. Others have argued that it was rather the precursor of the legal thriller.

Collins studied law, was admitted to the bar in 1852, and it is clear that his legal background had a strong influence on his writing.

Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White was revolutionary when it was published in 1859. Since then, it has been adapted for TV and film over and over again.

The latest adaptation is a BBC One TV series produced in 2018, and shown in America on PBS, with Jessie Buckley as Marian Halcombe, Olivia Vinall as Laura Fairlie, Ben Hardy as Walter Hartright and Dougray Scott as Sir Percival Glyde.

Collins was particularly fond of Paris

Collins visited Paris on several occasions, sometimes with Charles Dickens, his travel buddy.

Both “bon vivants”, with a taste for fine wine, champagne, French food, and most certainly also women, they would, one presumes, not linger too long around the museums and galleries, preferring instead to dine together, visit theatres and cabarets, or ramble the streets of seedy districts.

A visit to the bouquinistes

To start your tour of Paris in the steps of Collins, and before we dive into the darkness of the City of Light, a visit to the bouquinistes, the riverside booksellers seems perfectly appropriate.

They are located on the Right Bank, from Pont Marie to Quai du Louvre, and on the Left Bank, from Quai de la Tournelle to Quai Voltaire.

Collins liked to visit the bouquinistes. It is probably there that he bought a copy of Maurice Méjan’s Recueil des causes célèbres (1808), a collection of French legal cases that had been stirring public opinion.

Méjean relates the story of the Marquise de Douhault, a lady who had been interned by her family under a false name in an insane asylum, was presumed dead, escaped, but was never able to re-establish her identity.

It is not difficult to believe that the true story of the Marquise de Douhault was at least one of the sources of inspiration for The Woman in White.

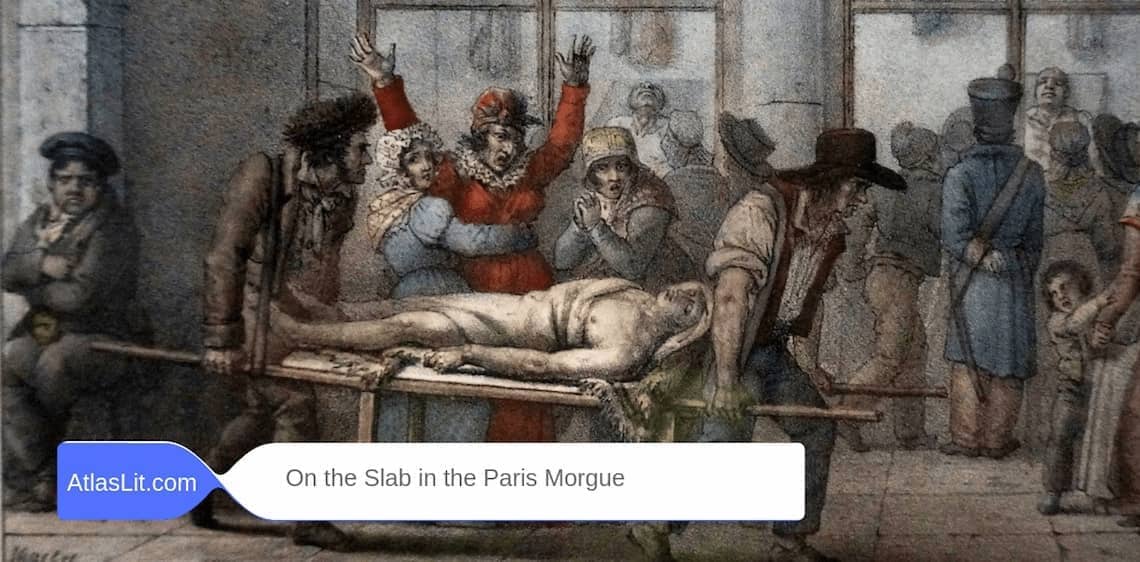

Imagine the Paris Morgue

Another place of interest for Collins, like for thousands of people, tourists and Parisians alike, was the very popular sightseeing venue of the Paris Morgue. It was a show that anyone could afford, rich and poor, as it was free.

Drawn by the morbid erotism of the naked dead bodies, a crowd of curious, including entire families, flocked to the Morgue every day.

The number of visitors reached more than one million people in the best years. It was so popular that every tourist guidebook mentioned the Morgue as a must-see place alongside the Tour Eiffel or the Catacombs.

The opening of the Morgue to the public was decided by the authorities in response to the difficulty they were facing in identifying the vast number of corpses picked up off the streets or pulled out of the Seine. The public was called in to help with their identification.

The most enlightening description of the Morgue experience comes from the French writer, Emile Zola, who wrote in his novel Thérèse Raquin (1868):

“The Morgue is a sight within reach of everybody, and one to which passers-by, rich and poor alike, treat themselves. The door stands open, and all are free to enter. There are admirers of the scene who go out of their way so as not to miss one of these performances of death.

If the slabs have nothing on them, visitors leave the building disappointed, feeling as if they had been cheated, and murmuring between their teeth; but when they are fairly well occupied, people crowd in front of them and treat themselves to cheap emotions; they express horror, they joke, they applaud or whistle, as at the theatre, and withdraw satisfied, declaring the Morgue a success on that particular day.”

In the final scene of The Woman in White, the villainous Count Fosco, having been stabbed and dragged out of the Seine ends up in the Paris Morgue:

“There he lay, unowned, unknown; exposed to the flippant curiosity of the French mob!”

Collins undoubtedly drew upon his memory of the several visits he made to the Morgue, which he described in letters to his mother:

“… a dead soldier laid out naked at the Morgue, like an unsaleable cod fish – all by himself upon the slab. He was a fine muscular old fellow who had popped into the water in the night and was exposed to be recognised by his friends.”

…and in another letter to his mother Collins wrote:

“On returning from the Beaux Arts I looked in at the Morgue. A body of a young girl had just been fished out of the river. As her bossom was “black and blue” I suppose she had been beaten into a state of insensibility and then flung into the Seine. The spectators of this wretched sight were, for the most part, women and children.”

Let’s head to the Quai du Marché-Neuf, on the Île de la Cité, right next to the Seine. You cannot visit the Morgue as it is not there anymore, but you can walk on the quai where it stood between 1804 and 1860 when it served as décor to the final scene of The Woman in White.

With a bit of imagination, you might visualise how the place looked like at the time. Perhaps, who knows, you might encounter a ghost or two from centuries past.

The Morgue was then moved to a larger and more modern building on the Quai de l’Archevêché, close to the cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris, where you can now enjoy the pleasant Square de l’Île de France.

Finally, in 1907, it was closed to the public for reasons of “moral hygiene”. It is now called the Institut de médecine légale, at the Quai de La Rapée, where you will not be welcome to visit unless, of course, you are a forensic doctor, in which case your French colleagues might let you in.

And yet, the fascination with death and the macabre, intrinsic to the human species, continues to lead hoards of tourists to visit another creepy place today.

The Paris Catacombs

Under the city of Paris lays a gigantic labyrinth of underground tunnels. The Paris Catacombs were once quarries used throughout the centuries to extract the rocks necessary to build the city.

It is 278 km in length (not including the sewage system), although only a small portion of it is open to the public.

Where place Joachim-du-Bellay and the Fontaine des Innocents now stand, there used to be a cemetery in which generations and generations of Parisians were buried.

Initially, Les Innocents was a cemetery with individual sepulchres only and the Church was making good money with burial fees. Later, it became a site for mass graves, where the poor would be buried for free in common pits, which could hold about 1,500 bodies each. Things got out of hand.

At the end of the 17th century, conditions became untenable due to overuse and incomplete decomposition of bodies. Imagine the stench! It was time to take action, the authorities decided.

The Cimetière des Innocents was closed and most bodies were exhumed; the bones moved to the Catacombs. The bodies that had incompletely decomposed and had reduced into large deposits of fat, were collected and turned into candles and soap. As for the cemetery, it was replaced by a herb and vegetable market.

The Paris Catacombs, a popular space in Paris since it opened to the public in 1809, had been visited by Wilkie Collins and his friend Charles Dickens.

Nowadays, more than five hundred thousand people go down the long stone stairwell every year to see the remains of millions of Parisians; among them, probably, those of François Rabelais, Jean de La Fontaine and Charles Perrault.

A visit to the Catacombs will offer you, your friends and family, a thrill that is certainly not as intense as the one visitors of the Morgue experienced, but it is the closest you will find in today’s Paris.

The entrance to the Catacombs is at number 1, avenue du Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy. That’s where the tourists go for the official and perfectly legal tour that lasts 45 minutes in the galleries 20 metres under the Place Denfert Rochereau.

But there are many cataphiles in Paris who use secret entrances and spend much time in the huge maze of tunnels far away from the tourists.

Despite the illegality of doing so, artists have used the walls to create their graffitis, cinephiles have built movie theatres, and counter-culture groups have held concerts deep beneath the Parisian streets.

A Museum for crime nerds

Before heading to the Catacombs, you might want to head first to the Musée de la Préfecture de police, a short stroll from the Île de la Cité, at 4, rue de la Montagne Sainte-Geneviève.

The Museum offers a fascinating journey through centuries of regicides, blood crimes, deaths by poison and scams investigated by the Paris police.

While it is not sure that Collins visited the Musée de la Préfecture, it would have been just his cup of tea, given his interest in legal cases and forensic science. It certainly is an amazing place and there is no entrance fee. A must for crime nerds!

The revolutionary prison of La Conciergerie

If instead, you prefer to stay a bit longer on Île de la Cité, head to La Conciergerie at 2, boulevard du Palais. There, at the time of the French Revolution, no less than 2,700 people awaiting the guillotine were imprisoned in just two years. Marie-Antoinette, whose cell you can visit, and Robespierre have been detained there before their execution.

The French revolution had a profound effect on British literature. Charles Dickens setting of A Tale of Two Cities (1859) was doubtless inspired by Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution (1837), but it was also inspired by Collins’s short story “The French Governess’s Story of Sister Rose” set in revolutionary France.

It is through a curious accident of history that some of the bones of both victims and executioners of the French Revolution have been buried together… in the Catacombs!

The Book

You can find the book on Amazon.