The search for Cloudstreet

“Perth is the biggest country town in the world trying to be a city. The most isolated country town in the world trying to be the most cut-off city in the world, trying desperately to hit the big time.

Desert on one side, sea on the other. Philistine fairground. There’s something nesting here, something horrible waiting. Ambition, Rose. It squeezes us into corners and turns out ugly shapes.”

This is how the city is described by Toby Raven, one of the characters of Cloudstreet.

Nowhere in the world like in Australia, and in particular, in Perth, the state capital of Western Australia, does time and space collide with such brutality.

One way to understand this is to read Cloudstreet by Tim Winton, one of the most popular Australian novels ever written.

Perth by night – Pixabay

Cloudstreet tells the story of two working-class families, during the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s.

Forced to move to Perth from their bush town of Geraldton and Margaret River, due to tragedies and poverty, the Lambs and the Pickles end up sharing a decrepit weatherboard house on Cloud Street in Perth.

Loss of an era and a place

Though the actions of the story span over a period of twenty years, between 1943 and 1964, the novel’s background takes us back as early as the 1890s when Lester Lamb, one of the main characters, was born.

At that time Lester was born, Australia was already a very urbanised society. Yet its poets created a national myth based on the people and landscapes of the bush – a myth still very much alive in today’s Australia.

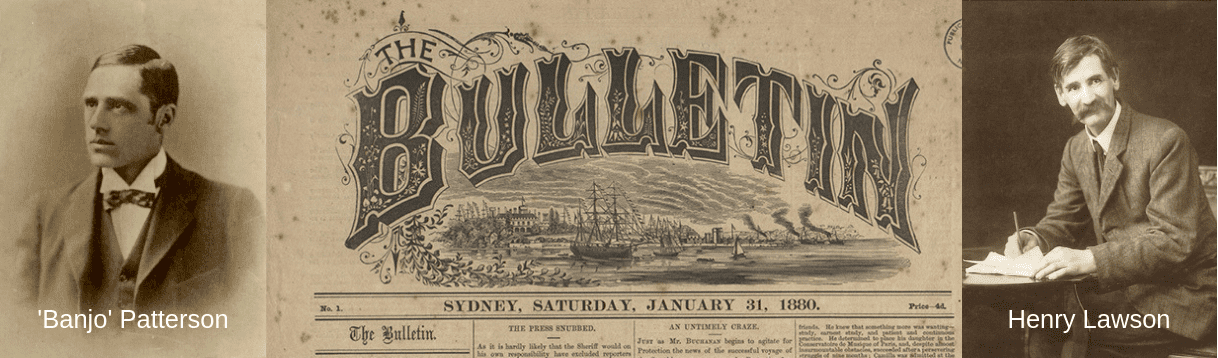

On 9 July 1892, Henry Lawson published a poem in The Bulletin magazine entitled “Up The Country”.

Beginning with the verse “I am back from up the country—very sorry that I went”, Lawson’s poem attacked the typical “romanticised” view of bush life that was prevailing at the time.

Banjo Paterson, another iconic Australian “bush poet”, claimed that Lawson’s view of the bush life was full of doom and gloom.

He published his reply to Lawson’s poem in the Bulletin. Titled “In Defence of the Bush”, his poem finishes with the line “For the bush will never suit you, and you’ll never suit the bush.”

The controversy between the two poets, known as the “Bulletin Debate”, lasted three years.

It was a clash between two representations of Australia, between a demonised city life and the innocence of the bush, between upper and lower classes, between settlers and working-class people. What both representations had in common, is that they largely skirted around Australian convict past and the incredible suffering inflicted on the Indigenous.

Does Winton pull back the Great Australian Silence blanket and expose the unresolved trauma of Australia’s past? Maybe, but only very partially. One thing is sure: through the use of symbolism and metaphors, Cloudstreet shed a light on what is repressed in the Australian unconscious.

The search for belonging

One of the reasons for the success of Cloudstreet is that it recreates a feeling of loss for an era and a place for which many feel a great nostalgia.

In Cloudstreet, Winton focuses on themes remanent of the Australian past, the colloquial speech, the endurance of the Aussie battler, mateship and larrikinism.

In fact, all the characters are haunted by the past, even the house!

The house of number one Cloud Street is a metaphor for Australia. Just as the convicts were transported from Britain to Australia against their will, their misfortunes forced the Lamb and the Pickles families to move into it.

They end up in this “great continent of a house” that “doesn’t belong to them”, “like fearful first settlers.”

Winton said in an interview that the house “doesn’t want the Lambs and the Pickles; it wants to shrug them off all the time. It’s strange and scary, and totally alien to them and resistant, and the continent is that way and in lots of ways remains that way for us.”

Like Australia, the house on Cloud Street has a tragic, shameful history.

Like all Australian houses, it is built on land that was stolen from Aboriginal people.

It is a former mission house, which was used to train ‘stolen generation’ Aboriginal girls, forcibly removed from their families. It was run by an elderly widow, a “very respectable woman” who “aimed to make ladies of them so they could set a standard for the rest of their sorry race.”

One of the young girls committed suicide ingesting ant poison in the library of the house.

A few weeks later, it is the turn of the elderly widow to die:

“She was at the piano one evening a few weeks after, mulling over the possibilities for diversion, when her heart stopped. She cried out in surprise, in outrage and her nose hit middle C hard enough to darken the room with sound. Her nose was a strong and bony one, and there was middle C in that library until rigor mortis set in.”

The sound of middle C that vibrates through the house and the ghost of the young Aboriginal girl are reminders of the barbarity of the treatment inflicted on Indigenous people. Australia’s past is part of the present of the Lamb and Pickles families.

An Aboriginal man, the “blackfella”, appears at key moments during the story and acts as some kind of counsellor and a protector concerned by the wellbeing of the two families. Sensing the tragic events that happened in the house, he is repelled by it:

“He moved back carefully as if moving back in his own footsteps, his eyes roving about all the time from wall to ceiling to floor, and as soon as he was over the threshold he turned and ran.”

However, the ghost of the Aboriginal young girl and the spectral “blackfella” are more figures than characters in the novel. They are unreal and seem to no longer have a place in the material world.

They play a peripheral role, removed from the action; similar to the one played even today by Indigenous people, forced to live in the fringes and experiencing disadvantage and injustice.

In interviews, Winton explained that “White Australia should value Indigenous culture highly”.

His position regarding Indigenous ownership and belonging is representative of many non-Aboriginal Australians. While they recognise that the land they live in was stolen, they also feel a strong sense of belonging to their country:

“When I got to Europe I knew the moment I set my foot down that I wasn’t European. I’d been brought up all my life to think that I was a European … I felt torn, almost, like torn out of the soil from home … I knew that if I stayed away too long I’d be adrift, and I felt like I was going to wither up and die.

I know this is where I belong. I know my continent, I know my country … No-one’s really going to be able to convince me that I don’t belong here … I wouldn’t say it’s a kind of new Aboriginality, I wouldn’t even feel that I had to even chase after the term, but it’s a feeling of belonging … I’m not embarrassed about coming from here, although I’m ashamed of the way my forebears have brought me into the country … I’m not ashamed to be here as a white Australian.” – Tim Winton

Cloudstreet is more than a beautifully written family saga. It is about the brutal treatment of Aboriginal Australians and about the White Australians trying to make peace with the past and develop a sense of belonging.

It is also about the nostalgia for the life in the outback and the experience of working-class people living in an inner suburb of Perth that was changing rapidly.

The end of innocence

Cloudstreet ends in 1964, the year Eric Cook, the Nedlands Monster becomes the last man to be hanged in Western Australia. Eric Edgar Cooke was Perth’s, and Western Australia’s, most notorious serial killer.

From the mid-1950s until his arrest in 1963, Cooke terrorised the city. He committed 250 robberies and 22 violent crime, eight of which resulted in deaths. Many of Cooke’s crimes occurred in Perth’s affluent western suburbs, such as Cottesloe and Nedlands. This is why the killer was dubbed “The Nedlands Monster”.

The description of the Nedlands Monster as one of the characters in Cloudstreet translates the fear the city shared at the time:

“[A] small man creeps through the back lanes between bin and gate and bloating fences itching with an inexplicable hatred … hating you, every one of you as you sleep moaning and turning beneath your sheet behind your flywire, past you as you sleep open on verandahs and on back lawns in the countrified manner you cling to. Oh, what hurt and malevolence glows in that shambling shape of a man … rolling wherever the hot headachy desert wind blows him: West Perth, Dalkieth, Shenton Park, Subiaco, Mosman Park … Against his chest he carries a rifle.”

For its inhabitants, Perth was a different city before and after the Cook murders. They mark the loss of security, optimism and innocence prevailing until then in a town where it was not unusual for people to leave their doors unlocked. The Nedlands Monster fulfils Perth’s ambition of a country town that wanted so much to become a city.

“The town is in a frenzy down there. This is what it means to be a city, they say, locking their doors and stifling behind their windows. On the streets, at night no one moves. No one goes out. There’s a murderer out there and no one knows what he wants, where he is, who he is, and why he kills. This is Perth. Western Australia, whose ambition knows no limit. And the streets are empty.”

Quick Lamb, who became a police officer, one of the many assigned to try to catch the Nedlands Monster, is present when the killer is finally caught. He is struck by his banality – an ordinary husband and father of seven.

“But there’s no monsters, only people like us. Funny, but it hurts.”

Suburban life

The characters feel that they do not belong in the house. They also struggle to adapt to the inner-suburban environment, which also functions as a metaphor for the struggle of non-indigenous Australians to adapt to life on a new continent.

However, the place where Cloudstreet is located is described more like a village than a suburb, and when the Lambs open a shop in their front room it serves as a meeting place and creates a sense of community. It is an inner suburb, where life was very different from the one in the anonymous new suburbs being built outside of the city, on land reclaimed from the bush.

When the opportunity presents itself to move to the new suburbs, the characters are first tempted but feel they do not belong there and prefer to remain together in Cloud Street.

Although Winton has never revealed which street or suburb inspired him as the location for number one Cloud Street, many are convinced that it would have been found in Perth’s inner-suburb of today’s West Leederville.

Leederville formed part of Boorloo, the tribal land belonging to the Mooro, one of the Noongar indigenous clans based around the Swan River, which were known collectively as the Whadjuk.

Lake Monger in Leederville was named after a settler, John Monger. It was known as Galup by the Noongar and used as a campsite, as well as for hunting and fishing until the arrival of the settlers.

Aboriginal resistance to the invasion of their land was quelled in 1834 after a bloody confrontation known as the Pinjarra Massacre.

Much later, in 2006, the Federal Court of Australia would pass a judgment recognising Noongar native title over the Perth metropolitan area; a judgement that would be overturned on appeal in 2008…

In December 1828, the British Colonial Office established a colony at Swan River as the first free settlement in Australia.

Leederville was named after the name of one of the settlers, William Leeder who was granted a parcel of land there after he arrived in Australia.

As the settlers needed labour to help them develop land that proved more difficult to exploit than the exaggerated claims of riches to be found in the “land of promise”, the British government accepted to send convicts to the Swan River Colony.

That’s when Perth really started to develop. Between 1850 and 1868, 9721 convicts were transported to Western Australia on 43 convict ship voyages.

Around that time, the local wetlands and lakes in the Leederville area were drained to allow the development of dairy and poultry farms, as well as market gardens.

Market gardening in Perth was done almost exclusively by Chinese people. In Leederville, these gardens were located along Oxford Street.

Some of the gardens were exploited until the 1960s when the land was requisitioned for the construction of the Commonwealth Games facilities held in Perth in 1962 and for the construction of the Mitchell Freeway in 1974.

In the latter part of the nineteen century, the gold boom saw thousands of prospectors from overseas and interstate arrive in Perth. Its population grew from 6,000 to around 87,000.

Wealth from mining also meant that a lot of buildings were knocked down in the inner suburbs. This explains why Perth, a city constantly transforming itself through the forces of profit and “progress” has far less heritage-style buildings than other cities in Australia.

Post World War II, Perth saw another population boom with the arrival of migrants from Europe, predominantly from Greece, Italy and Yugoslavia.

This is also the time when the gentrification process of the inner suburbs started.

Sam Pickles considered selling Cloudstreet and moving to a new suburb like Rose and Quick were planning to do.

“All the old houses were coming down and salmon pink duplexes were going up in their place.”

That’s when the Indigenous man appears to Sam, and tells him:

“You shouldn’t break a place … Too many places busted … You better be the strongest man.”

The River

In Cloudstreet, the river is where many important things happen. It meanders through the lives of the Lambs and Pickles families.

The river brings the Perth people together at a time when most suburbs were strung along its banks. It connects the working-class suburbs such as West Leederville with the privileged enclave of Nedlands and Dalkeith, with all classes gravitating to its banks for prawn fishing or picnicking.

“The river was broad and silvertopped and he knew its topography well enough to be out at night, though the old girl would have had a seizure at the thought. He never got bored with landmarks, the swirls of tideturned sand, armadas of jellyfish, the smell of barnacles and week, the way the pelicans baulked and hovered like great baggy clowns. He liked to hear the skip of prawns and the way a confused school of mullet bucked and turned in a mob. From the river you could be in the city but not on or of it.”

The World of Cloudstreet

Cloud Street never existed, but it could have been one of West Leederville streets that branch out of Railway Parade.

West Leederville is a suburb northwest of the central business district of Perth and is within the Town of Cambridge. It used to be integrated with Leederville (now within the City of Vincent) prior to the construction of Mitchell Freeway through the suburb.

In the novel, Lester suggests opening a store in the Lamb’s half of number one Cloud Street. “ I’ve cottoned on to somethin”, he tells his wife Oriel, “there’s no corner shop this side of the railway line”. Oriel replies: “I know, I’ve carried the groceries back from Subi”.

In Subi (Subiaco) is the football ground mentioned in Cloudstreet. The Subiaco Oval will be wiped out completely in late 2018 or early 2019 and is to be replaced by housing and commercial development, so you probably won’t be able to visit it.

To reach the Swan River, a favourite place for the Lambs and the Pickles, they would have had to go through Subiaco.

Visit West Leederville

Tucked away between the railway line, Lake Monger and the freeway, it is an interesting part of Perth to visit and get a feel of the world of Cloudstreet.

The Cambridge Heritage Trail would take you to locations of historical significance in West Leederville, providing an interesting insight into the life and places that are part of the world of the Cloudstreet’s mob.

From West Leederville railway station, you could walk down one of the streets that lead to Lake Monger – Tate, St Leonards, Northwood or Kimberley, where Cloudstreet may have been located.

Walk in the Lake Monger Reserve

Associated with the lake is the Wagyl, part of Noongar mythology. The myth describes the track of a serpent, who in his journey towards the sea, deviates from his route and emerges from the ground which gives rise to Lake Monger.

In the 1920s, the lake and surrounding areas were still being used as a campsite by Noongars, in particular near Dodd Street and Powis Street.

Part of the land around Lake Monger was also used by Chinese market gardeners. From the early 1920s, the City of Perth started acquiring land around the lake. By 1928 the gardeners were gone and by 1930, 50 hectares of land had been bought by the Council to be developed as part of the Lake Monger Reserve.

With the construction of the Mitchell Freeway along the eastern bank of the lake in the late 1970s, much of the grassed recreation area to the east was cut off from the main body of Lake Monger Reserve.

The Whadjuk walking trails lie on Noongar land, connecting remnant bushland areas in the western suburbs of Perth. Even though these trails run through suburbia, you will learn a lot about the flora, fauna and Noongar culture, thanks to the information provided along the way and on the website.

The Swan River

To reach the Swan River, a favourite place for the Lambs and the Pickles, they would have had to walk through Subiaco. There are quite a few walking trails that you could follow to discover the suburb.

On the riverside, there are some interesting places connected to Cloudstreet.

In the suburbs of Dalkeith, lies Sunset Hospital, a health facility built in 1904 and closed in 1995. With 18 buildings, it is one of the largest heritage places in the Perth metropolitan area.

The Sunset Hospital has a fascinating history, in which recently, even a Malaysian Sultan played a role. Many unsuccessful gold diggers were institutionalised at Sunset.

The complex also housed Samuel Speed, one of the last convicts to be transported to Australia. It was also one of the main facilities that housed and treated war veterans.

The filming of Cloudstreet TV series in 2009 took place on the Sunset Hospital site, where, after extensive location scouting proved unsuccessful, the whole house had to be built. But it is gone now…